IRES Seminar Series

Time: 12:30pm to 1:30pm (every Thursday)

Location: AERL Theatre (room 120), 2202 Main Mall

*********************************************************************************

*** CLICK HERE TO VIEW RECORDING (Harold 04:08-31:36 ) (Bronwyn 32:38-1:02:06)***

Chemical controversy: exploring scientific disagreements about the assessment of endocrine disrupting chemicals

Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) pose a wicked dilemma for science and regulation. EDCs interact with the endocrine (hormonal) system effecting development and reproduction. They are constitutive of numerous products that promote health, nutrition and beauty; however, EDCs also pose a potential threat to human and environmental health. Globally, scientists lack consensus over how to assess EDC risk: some advocate for a precautionary, hazard categorization approach; others for a more permissive risk assessment approach. Each side accuses the other of being unscientific and biased. This controversy has exacerbated difficulties in developing EDC regulation. Our study employed focus groups with scientists supporting a hazard and risk approach. The findings reveal fundamental differences in the framing of the challenge posed by EDCs, including the nature of the EDC problem, influences on chemical policymaking, and the roles of scientists in supporting or impeding effective regulation.

Bronwyn McIlroy-Young

IRES MA Program

Bio:

Bronwyn is a second year Masters student at UBC working with Dr Gunilla Oberg at the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability. She received her Bachelors in Knowledge Integration from the University of Waterloo in 2018 with her honour’s thesis on weather and climate change communication. Bronwyn’s research interests include risk perception, environmental justice, and values in post-normal science. Her Masters research explores scientific controversy around endocrine disrupting chemicals. She hopes her work will help to improve the conduct and communication of science for environmental policy.

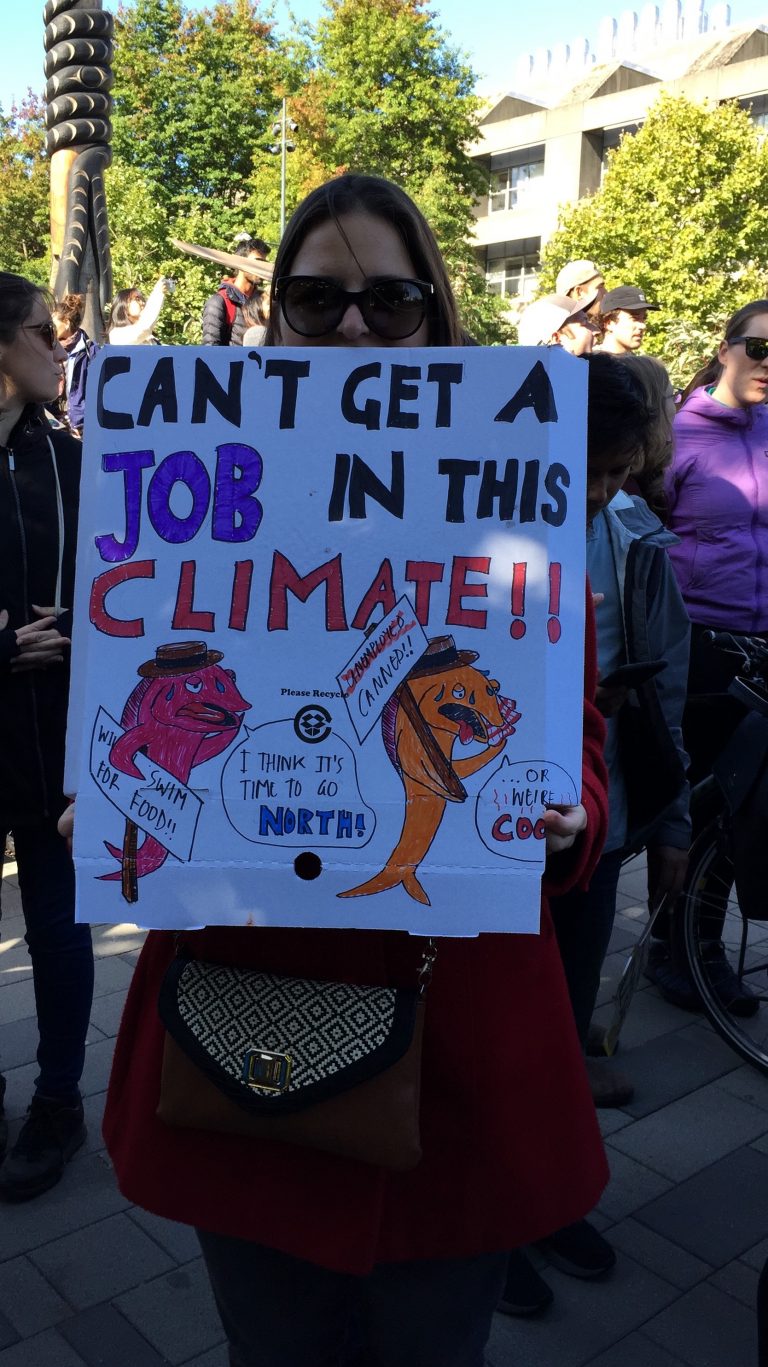

Using genetic distinctness to motivate people to conserve a widespread species

Conservation efforts have been particularly successful at bolstering rare species. Yet widespread, common species continue to decline, affecting ecosystems and human connections to nature—e.g., North America has lost nearly 30% of its individual birds in the last several decades. New methods to motivate people to protect widespread species are needed. Drawing on a relational values framework, I deploy a discrete choice experiment to test whether emphasizing genetic distinctness of local populations and a relational framing can motivate people to conserve a widespread species (Rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss). Modeling these data with a mixed multinomial logit model, I find that genetic distinctiveness and the relational reframing significantly increase the motivation to restore Rainbow Trout habitat. These findings suggest a new avenue for using an abundant resource (genetic data) to motivate conservation of a widespread, common species. These findings also demonstrate the fruitfulness of constructing environmental problems, and solutions, as relational.

Harold Eyster

IRES PhD Program

Bio:

Harold Eyster is a PhD candidate supervised by Dr. Kai Chan. Harold peers at environmental challenges through a relational lens: at the center of every environmental challenge or success are human–nature relationships. To understand these relationships, and how they might be harnessed to create a more verdant Anthropocene, Harold leverages methods from the natural and social sciences. Before coming to UBC, Harold received a BA at Harvard University. Harold brings his joy for birding, painting, Bayesian inference, and outdoor adventure into his research as much as possible, though he has yet to figure out a way of incorporating his enthusiasm for sourdough baking.